Intuition is the instinctive judgement of a particular scenario, often involving abstract reasoning. Part of intuition’s nature, which makes it distinct from other forms of human conduct, lies in its immediacy. Moral intuition is often challenged for reliability, especially as morality concerns the fundamental code of social behaviour. However, this essay argues that intuition paves the way for rational reasoning by committing an individual through expressing sentiments. It is worth trusting because it provides insight into foundational understandings.

The authority of reason and sentiment in intuitive moral decisions should be considered to establish the ground to champion moral intuition. Intuition precedes and leads to any possible room for rational thinking. Sentiment, the origin of intuition, is a “peculiar” feeling of approvals (love, pride) and disapprovals (hatred, humility) (Hume, 1739). These feelings are internal to individuals, and they are expressed through intuition. Consider a group of people capturing a cat, pouring gasoline, and igniting it. A spectator does not need to reason and “conclude” that this is morally wrong; a sentient being can “see” that it is wrong (Harman, 1977). When the spectator perceives the “prima facie” (at first sight) image of the cat burning, disapproval is indirectly brought upon themself after they intuit non-moral properties, such as the cat physically struggling, stimulating sympathy. Sentient beings can appreciate and empathize with the emotions of another individual. Owing to this ability, the spectator sympathizes with the suffering cat, and the desire to relieve the pain intuitively arises within himself. The prima facie property of intuition makes the expression of sentiment immediate; these emotions are original to sentient beings and, thus, natural to influence one’s moral judgment. Hume argues that morality cannot be grounded in reason; when an individual feels that reason opposes an impulse to act in a moral scenario, they had mistakenly treated a “calm passion” (1739) as rational thinking. Contrastingly, Kant (2019) argues that reason should have sole authority in moral decisions because they are unhindered by personal preference. Kant’s deontological approach determines that whether a moral guide can help an individual oblige to all the laws (e.g. Formula of Universal Law) is the only measure of its reliability. He did not examine other aspects that make intuition (which he dismissed as lacking “concept” and is thus “blind” (1929)) a viable guide, such as immediacy and its unique ability to motivate, empowered through the expression of sentiments.

Reason rarely opposes intuition because it derives from sentiments one feels at first sight of an experience. Hume (1739) describes passions as the “original existence”, and he concludes that reasons are mere backings of one’s emotions. A priori inferences – knowledge independent of experience (Russell, 2024) – are limited in guiding intuition since drawing upon them and applying them through systematic reasoning takes time.

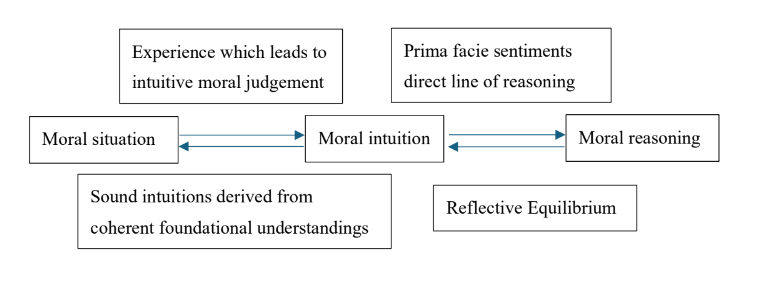

However, intuition can lead the development of reason, which does not require immediate responses. The roles of reason and passion are different; sentient intuition is the precursor of rational reasoning. Experience and perception trigger a chain reaction of emotions converted into moral decisions. Rational deliberation would align with the immediate reaction. The “is-ought” (Hume, 1751) desires motivate an individual to act with immediacy in moral intuitions; “to make a moral judgment is to detect, by means of a sentiment, the operation of a virtuous or vicious quality of mind” (Wilson and Denis, 2022). Beliefs alone (rather than sentiments) are not powerful enough to motivate and commit someone to a situation separate from themselves, but reason can check intuitive judgements without requiring the same immediacy. Intuition devotes an individual to a certain situation and bonds to the externals through virtue and vice. Therefore, it is a viable and dependable source of moral knowledge, especially under instantaneous circumstances where intuition precedes elaborate rational reasoning.

Criticisms of intuition’s reliability suggest that it lacks “empirical justification” (Pust, 2019). However, the moral “oughtness” brought upon an individual through immediate senses does not require empirical proof. “Virtues” and “vices” (Hume, 1739) are self supportive because none of one’s views can be solely rational, and the process of judging intuition is through reasoning, but it is also heavily influenced by intuitive emotions. Consider the basic moral intuition, “the statement ‘killing innocent people is wrong’ is morally just’”. When intuitively assessing this sentence, one can instantly feel it is true. The intuitive sense, based on past experiences and extensive non-moral understandings of “killing” and “innocence”, provides prima facie justification. Afterwards, when one attempts to use reason to justify his intuition, one’s very approval of their intuitive judgement is also an expression of weak sentiments (or “calm passions”), requiring trust in the reliability of their own intuition. It is natural for someone to judge their internal intuition in the same way as they judge an external moral situation. So, there is justifiable circularity in the proof of intuition. The “circularity” does not imply that intuition is not a source of moral knowledge. Moore (1903) classifies goodness as a “sui generis” notion after concluding that it is not a property which can be defined through the scientific means; it can only be appreciated by and on its own. The same applies to intuition because the expression of sentiments is not based on any assertions other than foundational – “beliefs which are justified independently of their relations to other beliefs” (McMahan, 2013). This fundamental difference of proof (or the necessity of empirical proof, which intuition lacks) defines intuition as self-sustaining. Thus, it negates criticism and establishes intuition as a reliable moral guide.

Having considered intuition’s ability to commit an individual to a moral situation and lead lines of reasoning, its status as reflections of foundational principles and its flexibility to be modified makes it a trustworthy moral guide.

From a metaethical perspective, intuition can serve as an insight into an individual’s deepest cognition of moral values. Ross (1930) denied the possibility that humans always know the right action in every circumstance. The seven prima facie principles should only be treated as a general guide, not a realist doctrine. Intuition is, therefore, fallible. Research has found that in the trolley dilemma, participants tend to be more willing to pull the lever to save five people but not to push a man off the bridge to achieve the same results. More people are inclined to pull the lever in a trap door scenario, killing one man to stop the trolley, than to directly kill a man on the bridge to halt the trolley (Stratton-Lake, 2020). Rationalists criticize moral intuition for not being a reliable guide because emotions hinder the consistency of one’s decision when faced with different degrees of engagement, which alters the desires one feels in moral dilemmas.

Nevertheless, this does not compromise intuition’s status as an individual’s sound guidance. Intuition constantly evolves as an individual gains experience and, in this process, adjusts values and consequent intuitions. The impact of virtues and vices is especially apparent when one feels an emotion from a “general point of view” (Hume, 1739). When a baby is taught that “hurting others is wrong”, their intuition might not be so strong as to form desires to actively stop them from hitting someone; it is only after they feel the vice (pain of getting hurt by others) or the virtue (happiness from stopping damage), his mind truly accepts the belief. Their standpoint shifts to a general one as they understand the moral principle from a broader perspective (one that is not limited to their own). This is done by them expressing sympathy and concern, and their sentiments turn their understanding into firm intuitions in similar future scenarios.

As it happens with the baby, experiences accumulate, and individuals develop the ability to compare their intuitive and general understandings. Through this process, one can amend one of the understandings to resolve one’s subsequent encounters with similar situations with more coherent judgements. To examine how the progression of moral decisions is done through internal reflections, Rawls (1971) constructed the “Reflective Equilibrium” model, which can trust moral intuition while adjusting foundational understandings in a particular moral situation, or vice versa in another. It is not meant to justify intuitions directly; instead, it can tune and filter moral intuitions to make judgments more reliable. Through this model, intuitions are trustworthy sources of moral knowledge because they point back to foundational principles. As an individual gains experience, fine calibrations make intuitions increasingly reliable.

Reflective equilibrium encourages vertical thinking. “Vertical” refers to foundational understandings at the core of one’s internal moral values, while intuition is the actual carrier of these understandings, interacting with externals and gaining experiences. Even foundational understandings, which can be considered sources of intuitions, are challenged as individuals apply their intuitions in moral situations. Intuitions feed back knowledge gathered in specific scenarios and expose foundational understandings to new changes and possibilities. There is a process of induction and referencing which requires an individual to be ready to adjust the balance of authorities in particular cases. Consider an application of reflective equilibrium on whether lying is morally right or wrong. In a normative case, when A lies to B, C, witnessing this, would intuitively think that A is in the wrong; C forms an intuition of vice based on their deeper understanding that “lying is wrong.” In this case, the particular intuition is concordant with the general foundational understanding. However, when external information is added to the scenario, say that B is dying and doctor A lied to B to save them from mental distress, C is likely to form a different intuition – A is doing the right thing to minimize B’s suffering. As this case creates tension with foundational understandings, C should adopt reflective equilibrium to either discard their intuitive judgement or add constraints to their general moral rule. Here, intuition is treated as a genuine source of moral knowledge because C’s foundational non-moral and moral values of “suffering is bad” and “minimizing suffering is good” both point to A being in the right. C would end up with a revised underlying understanding that “lying is wrong, unless when it is evident that telling the truth would prevent more pain than it would otherwise inflict on the individual.”

Thus, as this synergistic process repeats, intuitions and foundational understandings are both refined. Foundational understandings become more coherent after they have concurred, revised or expanded following the consideration of specific information. Intuitions become more reliable as they extract from the complex of foundational understandings that they have challenged. Through deriving intuitions, individuals at the same time justify their intuitive judgements. Reversely, intuitions are the starting points for discovering and perfecting moral principles. This dialectical method has the potential of getting closest to a set of moral truths. Internally, there is not a fixed set of rules; rather, the simultaneous development of the particular and the general results in an individual upholding increasingly robust foundational moral understandings, which in turn elicits reliable intuitions.

The proposed application of reflective equilibrium, involving moral intuition as a reliable source of judgement, entertains the possibility of combining guiding sentiments with successive reasoning. While moral intuition is conceded as fallible and that not all intuitions start as sound judgements, the aim is for knowledge obtained through experiences to cross-examine with existing foundational understanding and be improved to form coherent judgements over time. Moreover, Rawls’ “narrow reflective equilibrium” can be applied expansively in a social framework to achieve consistency and structure in the broader society by forming consensus. A better understanding of different perspectives increases the possibility of intuitions and emotions aligning among separate individuals, promoting harmony. This would further validate intuition as an insight into a set of true moral goodness that many can agree upon.

To conclude, moral intuitions should be trusted because they motivate individuals and commit them to act with immediacy. While achieving this, passions guide moral reasoning, which, through reflective equilibrium, evaluates the initial judgement and adjusts intuition if necessary. The fusion of prima facie with rationality, drawing from predominantly intuitive a posteriori experiences while refining them with a priori knowledge, will produce reliable moral judgements.

Bibliography

Harman, Gilbert. 1977. The Nature of Morality: An Introduction to Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hume, David. 1739. A Treatise of Human Nature. Vol. II and III. Edited by David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Hume, David. 1751. An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kant, Immanuel, Christopher Bennett, Joe Saunders, and Robert Stern. 2019. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. London, England: Oxford University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. 1929. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Norman Kemp Smith. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

McMahan, Jeff. 2013. “Moral Intuition.” In The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory, edited by Huge LaFollette. Wiley-Blackwell Press.

Moore, G.E. 1903. Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pust, Joel. 2019. “Intuition.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2019 Edition. URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/intuition/.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Ross, W.D. 1930. The Right and the Good. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Russell, Bruce. 2024. “A Priori Justification and Knowledge.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman (eds.), forthcoming. URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2024/entries/apriori/.

Stratton-Lake, Philip. 2020. “Intuitionism in Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2020 Edition. URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/intuitionism-ethics/.

Wilson, Eric Entrican, and Lara Denis. 2022. “Kant and Hume on Morality.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Fall 2022 Edition. URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/kant-hume morality/.

By Alida Chan

Alida Chan currently studies at Tonbridge School UK.